Review

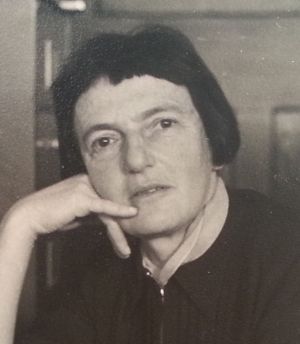

Charlotte Auerbach is also known as the "mother of chemical mutagenesis" for her research on the effects of mustard gas used in the two world wars as a chemical weapon.

Charlotte showed that this gas caused mutations in the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), with which she was doing research in her laboratory, i.e., it was a potent chemical mutagen. These studies led the scientist to seriously suspect that this gas was a dangerous mutagen.

Eventually, it was discovered that some commonly used therapeutic agents produce alterations in human chromosomes, causing heritable genetic disorders, and that there is a correlation between these chemical mutagens and some types of cancer.

Thus, the direct relationship between mutagenic agents and hereditary material has been demonstrated, as Charlotte Auerbach maintained throughout her life.

Justifications

- She was a precursor to the analysis and identification of toxic agents capable of interacting with genetic material and alterating it (mutations). She worked with Drosophila melanogaster (fruit flies).

Biography

Charlotte was born in Krefeld, Germany. From a Jewish family, Charlotte Auerbach studied Biology at the universities of Freiburg and Berlin. However, due to the wave of anti-Semitism that flooded Germany, in 1933 the young woman was forced to flee her country. She moved to Britain and settled in Scotland, where she was accepted as a PhD student at the Institute of Animal Genetics at the University of Edinburgh. Here she did his doctoral thesis, which she read in 1935, and remained attached to the center for the rest of her professional life.

Charlotte did not marry, nor did she have any biological children. Instead, she informally adopted two children she found through the NGO Save the Children.

Between the years of 1937 and 1940, Hermann J. Müller, who demonstrated that X-rays were a powerful mutagenic agent, enjoyed a stay at the Institute of Animal Genetics in Edinburgh and, according to Charlotte Auerbach's own words, this fact changed her life, as he introduced her to the fascinating field of mutagenesis.

In the early 1940s, Auerbach suspected that mustard gas was a highly toxic substance because it caused clear abnormalities in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, with which she was investigating in her laboratory. Careful experiments led the scientist to seriously suspect that this gas, used in two world wars as a chemical weapon, was a dangerous mutagen.

Auerbach's research on genetic mutations remained unpublished for many years, because the mustard gas work was considered classified information by the government. Finally, it was possible to publish it in 1947. After being an assistant instructor in animal genetics, Auerbach became an associate professor in 1947, professor of genetics in 1967, and ended her professional career as professor emeritus in 1969.

Works

- Auerbach, Charlotte (1961). The Science of Genetics. New York: Harper & Row.

- Auerbach, Charlotte (1965). Notes for Introductory Courses in Genetics. Edimburgh: Kallman.

- Auerbach, Charlotte (1976). Mutation Research: Problems, results and Perspectives. London: Chapman & Hall

Didactic approach

- The topic of mutagenic agents can be included in the subject of chemistry.

- Mutations and cancer appear in the subject of biology and geology of 3rd of ESO in the block of health; and also in biology and geology of 4th of ESO in the block about the evolution of life.

Documents